Folkestone Priory

Restoring the Church For All of Us

Make a Donation

Join the Movement

Folkestone Priory was founded in c630A.D. and is said to have been the very first Convent in Britain. The founder was Eadbald, King of Kent, son of Ethelbert the first English Christian King for Eanswythe daughter of Eadbald.

Like many other similar foundations, the Danes destroyed this church, dedicated to St Peter. The cliff on which convent was built was gradually undermined by the sea, and William Abrincis in 1138 gave the monks a new site, that of the present church. The convent buildings were erected between the church and the coastline. Being an alien priory the King occasionally seized it, when England was at war with France. However, the priory escaped the fate, which befell most of the alien priories in the reign of Henry V, having previously been made denizen and independent of the mother-house in Normandy. It continued to the time of the dissolution and was surrendered to the King on 15 Nov 1535. There are known to be at least twelve priors the final prior in 1535 being Thomas Barrett.

FOLKESTONE PRIORY

- H. Elgar (1919)

Although, with the exception of the church, almost the whole of this institution has disappeared, it may not be out of place to here set down what is known of it, as far as the writer is able; especially as it is most unlikely that excavations will be undertaken to expose any existing foundations for many years to come, for much of the site is occupied by the buildings known as Priory Gardens and a portion of the Vicarage.

St. Eanswythe’s nunnery stood near where the old Bayle Fort now is, and on this site was rebuilt a monastery in 1095. The monks subsequently asked to be removed out of the castle precincts; the present church was commenced in 1135. The two sites should not be confounded.

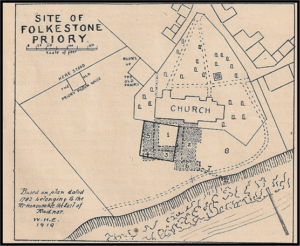

It is just possible that some particulars as to the first nunnery may be deduced from a study of the old maps and plans in the possession of the Right Honourable the Earl of Radnor, to whom the writer is indebted for the plan upon which the present observations are based. This plan is part of a survey made in 1782.

A glance at this plan will show that the paths through the churchyard are as they were, with the exception of one to the east of the church, which now passes outside the wall. The churchyard then had not been extended to its present size, a piece, stretching westwards to about where the priory pigeon house stood, has been added. It will be noticed that a square is drawn with a continuous line containing the tinted portions marked 1, 3, 4, and 5, This square occurs on the 1782 plan, and in it are these words, ‘Here stood the ruins of the old mansion house.’ It is this marked area and the two others to the northwest of it that give the clue to the plan of the priory. It will be just as well here to quote from Hasted’s History of Kent:

“The new priory was accordingly built upon the spot or plot of ground granted for this purpose by Sir William de Abrincis as above mentioned, close to the south side of the new church, with which, as appears by some doorways still to be seen in the wall of it, though long since filled up, the priory communicated and which thenceforward became the conventual church to it, both church and priory being dedicated to S.S. Mary and Eanswyth. “

We now pass to the time of the dissolution in 1535, and, still quoting from Hasted, ‘As soon as the King’s Commissioners had turned out the monks and taken possession of the priory, such part of the buildings the materials of which could produce any profit were ordered for the lucre of them to be taken down and sold.’

Two years after, ‘the house and site of it, with all houses the house and site of it with all homes, buildings, orchards, lands, and gardens within the precincts,’ were granted to Edward Lord Clinton. Within a few years of this event Folkestone was visited by Leland, and in his ‘Itinerary’ he says:

“The Toune shore be al lykelihod is marvelously sore wasted with the violens of the se; yn so much that there they say that one Paroche Chyrch of our Lady and another of St. Paule ys clene destroyed and etin by the se. Hard upon the shore yn a place cawled the Castle Yarde the which on the one side ys dyked and theryn be greate ruines of a solemne old nunnery the walles whereof yn divers places apere great and long British Brikes and on the right hand of the Quier a grave Trunee of squared stone. The Castel Yarde hath bene a place of great burial; yn so much as when the se hath woren on the Banke bones appere half stykyn out. The paroche chyrch ys therby made also of sum newer worke of an abbay. Ther is St. Eanswide buried and a late therby was the visage of a priory.’

Quite a graphic description of the state of the old castle and the ruins of the nunnery and a clear reference to the priory by the Parish Church.

Hasted gives a description of what he saw about 1800: All that remains of it and indeed has for a great number of years past, is a small part of the foundation, and an arch in the wall of it, about three feet above the ground, which is turned with Roman or British bricks of which there are several among the mixed foundations and under that one more modern of newer stone, seemingly for a doorway. From these ruins which are near the south-west corner of the church, where there is much uneven ground from the rubbish lying about it, there goes a large sewer of stone masonry, which runs underground slanting south eastwards, large enough for a man easily to creep through, the end of which appears, sticking out of the edge of the broken cliff over the shore, probably the same as Leland noticed.

Between the times of these two observers a mansion had stood upon the site of the priory. A very small sketch of this is to be seen on an old map at the Manor Office. Most likely a part of the priory was incorporated in the mansion. It should be noted that our plan of 1782 was made before Hasted published his ‘History of Kent.’

Probably some building stood near the spot marked with figure eight for the accommodation of the infirm, and it is possible that the prior himself had a separate house, which might have formed part of the house near the east gate of churchyard.

The view accompanying the plan is an attempt to show what the priory looked like in the 13th century to an observer northeast of the church. From this point the cloister and its adjacent buildings would not be visible, but both the other structures marked on the old plan could be seen.

The larger of these was most likely the guesthouse, for this was its usual position, and the pigeon house appears above the wall, which has been assumed connecting the west-end of the church with the guesthouse. In this wall the principal gate has been placed.

From what has been said of the history of the church in the previous article the changes in its appearance are all accounted for.

Mr. H. O. Jones, the Deputy Borough Engineer, has kindly supplied particulars, which enabled the sites of the priory house and the guesthouse to be plainly described,

The pigeon house stood just in the shrubbery of West Cliff Gardens, close to the present churchyard wall; and the guesthouse occupied about half the space (the eastern half) to the right of the path leading from the church to West Cliff Gardens.

The Background

In 927 Athelstan (King of England 924 – 939) gave the site to the See of Canterbury so that religious worship could be established there. This church is thought to have been dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary and survived until1052 when Earl Godwin plundered Folkestone and destroyed the church in revenge for having been outlawed by King Edward the Confessor. The church must have remained in ruins until well after the Norman Conquest, for it was not until 1095 that the Norman baron Nigel de Mundeville, Lord of Folkestone, erected a new church and priory for Benedictine monks near the same site. This was an alien foundation as the Priory of Folkestone was a cell of the Abbey of Lonley or Lolley in Normandy and was dedicated to St Mary andSt Eanswythe, whose relics were deposited in the church.

Later Churches

The inroads of the sea and the instability of the cliffs caused problems and c1138 the then Lord of the Manor, William d’Averanche was petitioned to remove them to a safer site. Thus the present church of St Mary and St Eanswythe was founded and dedicated and a priory erected between the church and the coastline. This church was probably quite small and simple but in about 1180, side chapels were added to the chancel. The piers still remain crowned with capitals carved with still-leaf foliage, typical of the transitional period when Romanesque, or Norman, architecture was slowly giving way to Gothic. Today they support simple Early English pointed arches of two orders built after the French had destroyed the church by fire in 1216.

The supposed original font installed about this time may still be seen within the south aisle at the west end, although this has been out of use for centuries.

About the year 1236 Hamo de Crevequer, a Norman nobleman, Baron on Folkestone and Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports extended the chancel to the east to form a new and spacious sanctuary. Its style reflects the supreme period when first pointed Gothic had reached its most graceful. The elegant series of seven lancet windows surrounding the altar with their richly carved shafts and mouldings are comparable with the work in many of the great cathedrals, abbeys and churches of Europe.

The town of Folkestone was incorporated in 1313 by Edward II and from then onward the burgess met annually at the Churchyard Cross on the Feast of the Nativity of Our Lady (8th September) to elect the Mayor. This was later restated by his son Edward lll , whose name is engraved on the Town Cross. The present cross is a restoration of 1897, but the steps are mediaeval. The official stall of the Mayors of Folkestone may be seen at the head of the nave. It is decorated by an elaborately wrought brass mace-rest with the municipal seal of St Eanswythe. Until 1869 the Mayoral stall was situated under the tower but was moved during the restoration of the church.

Originally it was the burghers of the town who assembled at the Cross for the ceremony and some townspeople were able to publicly vote to decide the mayor. However, the event was later held inside the Church where voters had to register their votes properly. The ‘modern’ ceremony probably goes back only to the 19th Century.

The Mayor and civic dignitaries assemble at the Town Hall before proceeding to the Cross for the naming ceremony at 11am. During the procession through the Church they follow a member of the Clergy carrying the Town Banner. There then follows a service at the Church for the Mayor before the party returns to the Town Hall and the Town Banner returns to its display case in the Church.

The central tower was rebuilt at some time in the early to mid 15th century and raised to a greater height, possibly to provide a platform for a beacon to guide channel shipping. At that time there were three bells. Today there are eight dating from 1879, though a century earlier another peal of eight had been installed.

In a custom of the age each bell was engraved with a humorous couplet relating to their tuneful functions. Around the same time the spirelt (small spire) on the tower staircase was added and crowned with the gilded weather vane. The tower basement was adorned with a fine vaulted roof in stone.

In 1464 the south chancel was rebuilt and ten years later that on the north side was extensively altered and renovated when it was raised to the same height as the chancel and finished with an embattlement parapet.

Reformation

With the coming of the Reformation the old mediaeval Latin services gave way to the new English liturgy of the Prayer Book. Unfortunately much havoc was wrought inside our churches, both then and during the Civil War 100 years later by extremists who objected to all fine carvings, stained glass and beautiful things in general on the grounds that they were ‘popish’. Screens and altars were thrown down and the magnificent Segrave tomb c1350 in the chancel was grievously damaged.

The priory was suppressed finally in 1535 when it is said that it contained only the prior and one old sick monk.

After the Reformation the fabric of the church was sadly neglected. However some internal alterations were made with the introduction of pews and galleried and a plaster ceiling in the chance, ‘for warmth’!

The Herdson family commissioned an elaborate family monument in 1622 in the south chapel, using the classical style advocated by Inigo Jones. In November 1605 Joan Harvey the mother of the great William Harvey, died and her memorial brass is still to be seen, in its current position, on the south chancel wall by the vestry door.

By the early 18th century the west end of the nave must have been in a dire condition, for during the Great Storm of 1705 the two end bays were blown down. It was decided to rebuild only one arch and the west end was finished off with a long sloping barn like roof and three domestic sash windows.

So the church remained until the arrival of Thomas Pearce as Vicar in 1818 and in 1843, Reverend Pearce began a programme of restoration and repair.

When Matthew Woodward was inducted as vicar in 1851, he was appalled by what he saw and made extensive plans to restore not only the disfigured and truncated nave but also the church as a whole.

He ensured that the best craftsmen available carried out all the work undertaken using the best materials. He had the gift not only to inspire his congregation with the power of his sermons but also to encourage generous donations enabling him to rebuild and beautify the building to an extent rarely seen outside of a cathedral.

TIn 927 Athelstan (King of England 924 – 939) built a new church in Folkestone dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary. This church lasted until 1052 when Earl Godwin plundered Folkestone in revenge for having beenoutlawed by King Edward the Confessor.

The church must have remained in ruins until well after the Norman Conquest, for it was not until 1095 that the Norman baron Nigel de Muneville built a new church and priory (see notes).

Later churches

The inroads of the sea and the instability of the cliffs caused problems and during the 1140’s the Lord Manor William d’Averanche (see notes) was petitioned to remove them to a scare site. Thus in 1138 the present church of St Mary and St Eanswythe was founded and dedicated.

The d’Averanches’ church was probably quite small and simple but in about 1180, side chapels were added to the chancel. The piers still remain crowned with capitals carved with stiff-leaf foliage, typical of the transitional period when Romanesque, or Norman, architecture was lowly moving to Gothic (see notes). Today they support simple early English pointed arches of two orders built after the French had destroyed the church by fire in 1216. The original font installed about this time may still be seen within the south aisle at the west end, although this has been seen out of use for centuries.

During the first half of the 13th Century the church assumed the plan we see today, comprising a chancel of two bays with chapels, a centre tower and transepts, and a nave with four bays with aisles. The convent buildings were situated on the south side of the nave on the site of the Priory Gardens.

About the year 1236 Hamo de Crevequer, a Norman nobleman, Baron of Folkestone and Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports extended the chancel to the east to form a new and spacious sanctuary. Its style reflects the supreme period when first Pointed Gothic had reached its most graceful. the elegant series of seven lancet windows surrounding the alter with their richly carved shafts and mouldings are comparable with work of many of the great cathedrals, abbeys and churches of Europe.

14th century

The town of Folkestone was incorporated in 1313 by Edward 11 and from then until the Reformation the burgesses met annually at the Churchyard cross on the feast of the Nativity of our Lady (8th September) to elect the Mayor. The present cross is a restoration of 1897, but the steps on which it stands are mediaeval. The official stall of the Mayors of Folkestone may be seen within the Church at the head of the nave. It is decorated by an elaborately wrought brass mace-rest set with municipal seal of St Eanswythe.

It is believed that the Mayor Making ceremony originated in the year 1313; when King Edward II first granted the town a Mayor. This was later restated by his son Edward III, whose name is engraved on the Town Cross.

Originally it was the burghers of the town who assembled at the Cross for the ceremony and some townspeople were able to publicly vote to decide the mayor. However, the event was later held inside the Church where voters had to register their votes properly. The ‘modern’ ceremony probably goes back only to the 19th Century.

The Mayor and civic dignitaries assemble at the Town Hall before proceeding to the Cross for the naming ceremony at 11am. During the procession through the Church they follow a member of the Clergy carrying the Town Banner. There then follows a service at the Church for the Mayor before the party returns to the Town Hall and the Town Banner returns to its display case in the Church.

NB the Town Banner’s history remains a mystery with no current proof as to ownership. As the Banner is in desperate need of repair the Friends are attempting to get it repaired and restored.

The central tower was rebuilt about 1400 and raised to a greater height, doubtless to provide a platform for a beacon guide channel shipping. At that time there were three bells. Today there are eight, dating from 1879, though a century earlier another peal of eight had been installed. In a custom of the age each bell was engraved with a humorous couplet relating to their tuneful functions. Around the same time the spirelt (spire) on the tower staircase was added and crowned with the gilded weather vane. The tower basement was adorned with a fine vaulted roof in stone.

In 1464 the south chancel chapel was rebuilt and ten years later that on the north side was extensively altered and renovated when it was raised to the same height as the chancel and finished with an embattlement parapet.

With the coming of the Reformation the old mediaeval Latin services gave place to the new English liturgy of the Prayer Book. Unfortunately much havoc was wrought inside our churches, both then and during the Civil War 100 years later by extremists who objected to all fine carving, stained glass and beautiful things in general on the grounds that they were ‘popish’. Screens and altars were thrown down and the magnificent Segrave tomb in c1350, in the chancel previously damaged.

The priory was suppressed finally in 1534 when it contained only the prior and one old sick monk.

After the Reformation the fabric of the church was sadly neglected. However some internal alterations were made with the introduction of pews and galleries and a plaster ceiling in the chancel, ‘for warmth”! The henderson family commissioned an elaborate family monument in 1628 in the south chapel, using the classical style advocated by Inigo Jones. Earlier in 1605 Joan Harvey, the mother of the great William Harvey (see notes), died and her memorial brass is still to be seen on the south chancel wall by the door of the vestry.

By the end of the 17th Century the west end of the nave must have been in dire condition, for during the great storm of 17045 the tow end bays were blown down. It was decide to rebuild online arch and the west end was finished off with a long sloping barn like roof and three domestic sash windows.

By the early 18th century the west end of the nave must have been in a dire condition, for during the Great Storm of 1705 the two end bays were blown down. It was decided to rebuild only one arch and the west end was finished off with a long sloping barn like roof and three domestic sash windows.

So the church remained until the arrival of Thomas Pearce as Vicar in 1818 and in 1843, Reverend Pearce began a programme of restoration and repair.

Matthew Woodward Memorial Brass

When Matthew Woodward was inducted as vicar in July 1851 he was appalled by what he saw and made extensive plans to restore not only the disfigured and truncated nave but also the church as a whole. He ensured that the best craftsmen available carried out all of the work undertaken using the very best materials. He had the gift not only to inspire his congregation with the power of his sermons and sincerity of his ministry but also to encourage generous donations enabling him to rebuild and beautify the building to an extent rarely seen outside a cathedral.

The Windows of St Mary and St Eanswythe

The beautiful octagonal font of 1490 was enclosed by an elaborate brass and iron screen probably made by Skidmore of Coventry. The great brass lectern is by Jones and Willis and originally stood under the tower.

The 13th Century font with its ornate 19th century brass cover

(9)The North Aisle of the Nave. These two windows once depicted Archbishops: Theodore (602 – 690), Ethelred (c880), St Anselm (1033-1109), St Thomas aka Thomas a Becket (1170) and Archbishop Laud (1573 – 1644). The glass was by Hemmings and they were destroyed in WW11

North Transept – The Matthew Window. This was given in ‘ grateful recognition’ of the work done by Canon Matthew Woodward but sadly was destroyed during the last war and has been replaced by glass commemorating various notable Folkestone families.7

The Lady Chapel. All of these windows are by Kempe and depict in order from west to east: First St Gabriel, St Elizabeth) mother of John the Baptist) and John the Baptist himself; second three martyrs Saints Alban, Agnes and Faith and third the small window depicting St Anne the mother of Our Lady with Mary as a child. The east window over the altar depicts the Blessed Virgin Mary and the Holy Child flanked by both St Peter and St Michael.

The Chancel. The four lancet windows on the north and south sides are by Taylor and Co and show the Nativity, the Epiphany, the Purification and the Annunciation. The three lancet windows above the High Altar are by Kempe and depict in the centre the Crucifixion, on the left the Blessed Virgin with St Augustine kneeling and on the right St John with St Eanswythe kneeling. Higher up, the vessica (pointed oval) window depicts ‘The Majesty of Our Lord in Glory surrounded by angels, with his hand raised in blessing’ the glass is by Clayton and Bell (11).

The St Eanswythe Chapel. From east to west: the small lancet window depicts St Eanswythe with her pastoral staff and fish purse: St Eanswythe’s miracle of keeping the birds from the crops (replacing The Flight into Egypt which was destroyed in WW11) and a memorial window to those who gave their lives during WW11 (replacing the transfiguration destroyed in that conflict).

South Aisle of the Nave. From east to west: the three-light Children’s Window by Kempe showing Our Lord with children and Samuel and Timothy as children in the lower panels; The Communion Window by Kempe; the Confirmation Window by Hemming and the Baptism Window also by Hemming. These three windows depict biblical incidents complemented by Victoria images in the lower panels.

The west window of the South Aisle is the St John Window and depicts scenes from the lives of both St John the Baptist and St John the Evangelist.

Moving to the west end of the nave there are two delightful small memorial windows either side of the west door by Kempe depicting the Fall and Expulsion from Paradise.

Occupying the west wall is the Harvey Window. This was installed in 1874 to honour the Folkestone born physician, who in 1616 first discovered the circulation of the blood. The glass is by Kempe and the stone tracery by Stallwood. The subject is the Tree of Life and shows Our Lord crucified thereon. The branches include four healing miracles recounted in the Gospels.

The Baptistery. A pair of windows by Kempe, depict the mission of St Augustine with King Ethelbert on the left and St Augustine on the right. Above is a Rose Window depicting the Baptism of Our Lord. In the north wall is a small window containing recently discovered glass depicting St Peter with his crossed keys, which was hidden behind a staircase leading up to the gallery. It dates from about 1860

In 1858 Matthew Woodward was able to commence the rebuilding of the nave with the architect R.C.Hussey. The nave arcades were re-constructed exactly as they had been originally and a new and wider north aisle and transept were constructed.

The Stations of the Cross by Hemmings, who did most of the other murals, date from the early eighteen-nineties. They are thought to be unique with such detailed figures about one-third life size.

Matthew Woodward’s long incumbency of forty-seven years is commemorated by a brass on the floor of the chancel near the Communion rail. During this time he embarked on a series of schemes for enlarging and decorating the church. With furnishings and murals by a variety of artists and every window filled with stained glass, including Kempe’s magnificent Harvey Memorial Window of 1880, the building had been transformed by the time of his death in May 1898.

The Matthew Woodward Memorial Brass

Charles Eamer Kempe was born at Ovingdean Hall in Sussex, in a valley of the South Downs near Brighton. The youngest of the seven children of Nathaniel Kempe, JP. his mother was Nathaniel’s second wife Augusta, who was herself the daughter of a former Lord Mayor of London. Kempe was educated at Rugby and then Pembroke College, Oxford receiving his MA in 1862. A devout Anglo-Catholic with a particularly bad stammer, which would have proved very difficult for a career in the church, he therefore devoted his life to the cause of beautifying church buildings. First he entered the office of G. F. Bodley who was the son of the family doctor, he then spent some time with the stained-glass firm of Clayton and Bell in London, and eventually set up his own highly successful firm in 1866. The firm survived until 1934, and there is an English Heritage plaque on his former London home and studio at 37, Nottingham Place, Marylebone, W1

Kempe liked to work in late medieval/early Renaissance style and his work is also distinguished by its detailed face-drawing and shimmering greens. “He gave England some of the most glowing windows in our church,” says Arthur Mee ( a British writer and journalist of the period). The Kempe Studios supplied many cathedrals, too, and Kempe’s fame spread far beyond Britain, particularly to North America . He employed as many as a hundred men. Perhaps his most prestigious commission was for the royal mausoleum in Darmstadt, where he was asked to commemorate Princess Alice’s little son.

Clayton and Bell was one of the most prolific and proficient workshops of English stained glass during the latter half of the 19th century. The partners were John Richard Clayton (London, 1827–1913) and Alfred Bell (Silton, Dorset, 1832–95). The company was founded in 1855 and continued until 1993. Their windows are found throughout the United Kingdom, in the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

Clayton and Bell’s commercial success was due to the high demand for stained glass windows at the time, their use of the best quality glass available, the excellence of their designs and their employment of efficient factory methods of production.

They collaborated with many of the most prominent Gothic Revival architects.

The High Altar itself came a little later, probably about 1910. Its mensa (table) is formed by a massive slab of pink marble. This is supported on a base of carved English oak, which has five compartments with scenes in terra cotta of the life of Our Lord.

The most notable examples being by Kempe who executed the three altar windows and those in the Lady Chapel. Others were supplied by Clayton & Bell, O’Connor and Hemming.

The beautiful octagonal font of circa 1490 was enclosed by an elaborate brass and iron screen, which may be by Skidmore of Coventry. The great brass lectern is by Jones and Willis and originally stood under the tower.

The 14th Century font with its ornate 19th century brass cover

The High Altar itself came a little later, probably about 1910. Its mensa (table) is formed by a massive slab of pink marble. This is supported on a base of carved English oak, which has five compartments with scenes in terra cotta of the life of Our Lord.

The Stations of the Cross by Hemmings, who did most of the other murals, date from the early eighteen-nineties. They are thought to be unique with such detailed figures about one-third life size.

In June 1885, during the installation of Hem’s elaborate Sanctuary arcading of Derbyshire alabaster, with the Apostle mosaics designed by Capello, the workmen came across a small cavity in the north wall containing an ancient lead casket. Upon its removal and examination it was found to contain the remains of a young woman who had died in the 7th century. From the place of burial near the High Altar, the position of greatest honour and distinction in the church, it was concluded that here were the long lost relics of St. Eanswythe which tradition asserted had been hidden somewhere in or near the Parish Church at the time of the Reformation.

The remains were reverently interred in the place where they had been discovered still in their ages-old Saxon coffer, and enclosed behind an elaborate brass grill and engraved door. There they remain to this day, bestowing a rare distinction upon our church, which is one of the very few places remaining in this country, which has the bones of its patron saint buried within its walls.

Modern additions

The tradition of adornment and dignified worship initiated by Canon Woodward has been preserved and extended down to the present time. This venerable Parish Church now possesses among other things one of the finest collections of vestments and altar frontals in the south east, with notable examples by Bodley and Comper. This is a revival of the pre-Reformation tradition when Folkestone Church was famous for its rich vestments.

Among the altar plate is a magnificent Gothic Revival chalice of silver gilt and enamel work of French origin reputed to have once belonged to Cardinal Manning. The Jacobean Communion Cup with its standing cover, also of silver gilt, is hallmarked 1608. A more recent addition is the lovely hand-beaten silver altar book rest by Omar Ramsden, modern artist of great sensitivity.

In 1934 the Lady Chapel was restored and five years later

F. C. Eden was called in to design the magnificent carved and gilded reredos and stone altar.

The organ was first built by Hill in 1894 and rebuilt in 1931. During the latter part of the 18th century the organ stood at the west end of the nave. Later it was moved to a new site in the present Lady Chapel, before finally being rebuilt in its present position during the later Victorian period.

The vestries were extended in 1954 and contained some 16th century stained glass roundels said to have come originally from Canterbury Cathedral. These roundels and the screen in which they were mounted were badly damaged by fire in a recent arson attack but they were rescued and have been restored and can now be seen on display in the church. A few years later the generosity of the same donor rebuilt and extended the north-west porch which now forms the main entrance.

The splendid carved oak pulpit dating from 1913 was re-sited during the early part of 1973. In the mid-1990s three pews were removed from the head of the nave creating a space for the altar at the Sunday Parish Eucharist and for other services and presentations. Thus each passing age has left its mark upon this building.

The pulpit & St George’s Chapel

Generations come and go. Like a sentinel the old grey tower watches over them all as they pass. It has seen Folkestone as a sleepy little fishing village containing but a handful of folk develop into a spacious and fashionable Victorian watering place. In turn this has passed into history and modern times have witnessed the advent of a busy and thriving channel port and a popular seaside resort.

The 21st Century has seen the development of ‘The Creative Quarter’ in the Old High Street and Tontine Street in which the church plays its part hosting concerts and exhibitions and bringing people into this marvellous, historic building to absorb its atmosphere of centuries of prayer and to admire its architectural and aesthetic glories.

Yet through the centuries this ancient building has remained much as our forefathers knew it, the symbol of a living and changeless Faith, beckoning people to turn aside awhile from all the tumult of a tempestuous existence to enter in and find refreshment and renewal in Him who is indeed, the way, the truth and the life. Let us also turn aside and with them echo the praise of the Psalmist when he says:

‘Lord, I have loved the habitation of Thy House

and the place where Thy Honour dwelleth.’

We gratefully acknowledgerThe tradition of adornment and dignified worship initiated by Canon Woodward has been preserved and extended down to the present time. This venerable Parish Church now possesses among other things one of the finest collections of vestments and altar frontals in the south east, with notable examples by Bodley and Comper. This is a revival of the pre-Reformation tradition when the Folkestone Chrurch was famous for its rich vestments.

Among the altar plate is a magnificent Gothic Revival chalice of silver gilt and enamel work of French origin reputed to have once belonged to Cardinal Manning. The Jacobean Communion Cup with its standing cover, also of silver gilt, is hallmarked 1608. A more recent addition is the lovely hand-beaten silver altar book rest by Omar Ramsden, a modern artist of great sensitivity.

The organ was first built by Hill in 1894 and rebuilt in 1931. The organ stood in the Lady Chapel before being finally rebuilt in its present position in 1869.

In 1934 the Lady Chapel was restored and five years later F.C.Eden was called in to design the magnificent carved and gilded reredos and stone altar.

The Lady Chapel

In the Quinquennial Inspection Report of 2008 severe defects in the stonework of the Lady Chapel were identified and it was concluded that the leadwork on the roof was failing.

With the aid of grants, work was undertaken in 2011 to make good the exterior of the Lady Chapel and Internally, the Chapel was replastered in part, and redecorated, and the monuments repaired remain at low level.

The vestries were extended in 1954 and contained some 16th century stained glass roundels said to have come from Canterbury Cathedral .These roundels and the screen in which they were mounted were badly damaged by fire in an arson attack but were rescued and have been restored.

The splendid carved oak pulpit dating from 1913 was re-sited during the early part of 1973. In the mid 1930s three pews were removed from the head of the nave creating a space for the altar at the Sunday Parish Eucharist and for other services and presentations. Thus each passing age has left its mark upon this building.

Generations come and go. Like a sentinel the old grey tower watches over them all as they pass. It has seen Folkestone as a sleepy fishing village containing but a handful of folk develop into a spacious and fashionable Victorian Watering place. In turn this has passed into history and modern times have witnessed the coming and going of a busy and thriving channel port and a popular seaside resort.

The 21st Century has seen the development of ‘ The Creative Quarter” in the Old High Street and Tontine Street in which the church plays its part hosting concerts and exhibitions and bringing people into this marvellous, historic building to absorb its atmosphere of centuries of prayer and to admire its architectural and aesthetic glories.

Yet through the centuries this ancient building has remained much as our forefathers knew it, the symbol of a living and changeless Faith, beckoning people to turn aside awhile from all the tumult of a tempestuous existence to enter in and find refreshment and renewal in Him who is indeed, the way, the truth and the life. Let us also turn aside and with them echo the praise of the Psalmist when he says:

‘ Lord I have loved the habitation of thy House and the place where Thy Honour dwelleth’

We gratefully acknowledge Anthony Reader – Moore’s permission to reproduce his original text and Jane Palmer for the use of her photographs May 1973

Amended and adapted by Eamon Rooney June 2019

The pulpit and St George’s Chapel

Generations come and go. Like a sentinel the old grey tower watches over them all as they pass. It has seen Folkestone as a sleepy little fishing village containing but a handful of folk develop into a spacious and fashionable Victorian watering place. In turn this has passed into history and modern times have witnessed the coming and going of a busy and thriving channel port and a popular seaside resort.

The 21st Century has seen the development of ‘The Creative Quarter’ in the Old High Street and Tontine Street in which the church plays its part hosting concerts and exhibitions and bringing people into this marvellous, historic building to absorb its atmosphere of centuries of prayer and to admire its architectural and aesthetic glories.

Yet through the centuries this ancient building has remained much as our forefathers knew it, the symbol of a living and changeless Faith, beckoning people to turn aside awhile from all the tumult of a tempestuous existence to enter in and find refreshment and renewal in Him who is indeed, the way, the truth and the life. Let us also turn aside and with them echo the praise of the Psalmist when he says:

‘Lord, I have loved the habitation of Thy House

and the place where Thy Honour dwelleth.’

Anthony Reader-Moore

May 1973

Amended and adapted by Eamon rooney June 2019

We gratefully acknowledge Anthony Reader-Moore’s permission to reproduce his original text and Jane Palmer for the use of her photographs.

The Lady Chapel

In the Quinquennial Inspection Report of 2008 severe defects in the stonework of the Lady Chapel were identified and it was concluded that the leadwork on the roof was failing.

With the aid of grants, work was undertaken in 2011 to make good the exterior of the Lady Chapel and Internally, the Chapel was replastered in part, and redecorated, and the monuments repaired remain at low level.

The Lady Chapel and Reredos

The vestries were extended in 1954 and contained some 16th century stained glass roundels said to have come from Canterbury Cathedral .These roundels and the screen in which they were mounted were badly damaged by fire in an arson attack but were rescued and have been restored.

The splendid carved oak pulpit dating from 1913 was re-sited during the early part of 1973. In the mid 1930s three pews were removed from the head of the nave creating a space for the altar at the Sunday Parish Eucharist and for other services and presentations. Thus each passing age has left its mark upon this building.

The pulpit and St George’s Chapel

Generations come and go. Like a sentinel the old grey tower watches over them all as they pass. It has seen Folkestone as a sleepy little fishing village containing but a handful of folk develop into a spacious and fashionable Victorian watering place. In turn this has passed into history and modern times have witnessed the coming and going of a busy and thriving channel port and a popular seaside resort.

The 21st Century has seen the development of ‘The Creative Quarter’ in the Old High Street and Tontine Street in which the church plays its part hosting concerts and exhibitions and bringing people into this marvellous, historic building to absorb its atmosphere of centuries of prayer and to admire its architectural and aesthetic glories.

Yet through the centuries this ancient building has remained much as our forefathers knew it, the symbol of a living and changeless Faith, beckoning people to turn aside awhile from all the tumult of a tempestuous existence to enter in and find refreshment and renewal in Him who is indeed, the way, the truth and the life. Let us also turn aside and with them echo the praise of the Psalmist when he says:

‘Lord, I have loved the habitation of Thy House

and the place where Thy Honour dwelleth.’

Anthony Reader-Moore

May 1973

Amended and adapted by Eamon rooney June 2019

We gratefully acknowledge Anthony Reader-Moore’s permission to reproduce his original text and Jane Palmer for the use of her photographs.

content goes here. Edit or remove this text inline or in the module Content settings. You can also style every aspect of this content in the module Design settings and even apply custom CSS to this text in the module Advanced settings.

Click the link below to view:

Our Top Priorities

efficient heating

We all know that churches can be cold places due to the scale of the buildings, but it's not much fun to shiver in! The more efficient and cost-effective the heating system, the warmer we'll be.

the tapestry

The church is full of beautiful and intricate tapestries surviving so much through time and our aim is to make sure that survival is continued for many more visitors to enjoy.

The roof

The roof is obviuosly the most important strucure on the building, protecting all inside. We crucially need to complete all necessary repairs to make this 100% watertight.

Fundraising

Our constant. We are always looking for new and innovative ways to raise money. Join us and be part of the proud team looking after just one piece of Folkestone's heritage.

Join Us...

Get Involved

We Folkestonians cannot let neglect succeed in destroying our Church - the focal point of the town and it’s history - where fire and wars have failed. Once the Church has gone it will be gone for good. For the love of Folkestone we need to act now.

Give Today

Get In Touch

who we are

The Friends of St Mary and St Eanswythe Parish Church began on 21st March 2014 and is dedicated to the preservation of St Mary and St Eanswythe’s Church.

REGISTERED CHARITY NUMBER 1161358

what we do

Our sole aim is to raise funds all of which will be devoted to the upkeep of the building and to the furthering of public understanding of its history, architecture and significance.